The nature of Orthodox iconography is collaborative. The icon painter does not work alone, the continuity of the practice can only be contained by Holy Tradition sustaining its truth. Michael very much appreciated the wealth of information that he was introduced into on a deeper level of sacred tradition. He realized aspects of various cultures giving their own uniqueness to the style of the art form yet preserving an unchanging liturgical language.

We spent time with the book, Iconostasis, written by Father Pavel Florensky in the year 1922. Father Pavel wrote the book at Holy Trinity St. Sergius Monastery, Sergiev Posad, Russia, a place that I have been to perhaps a dozen times. It is Holy Trinity Church, one of the churches at the monastery, that houses the magnificent Rublev iconostasis along with the icon of The Trinity which Andrei Rublev was canonized after. The monastery represents a great cultural, religious and spiritual center in Russian history and in our current day.

The book contained a passage that seemed to resonate with the development of an iconographer and the course of disciplined study. Father Pavel tells his spiritual children, “Anyone who does things carelessly also learns to talk carelessly. But careless, unclear, inexact talk drags into its carelessness and unclarity an idea. My very dear, dear children: don’t let yourselves think carelessly. An idea is God’s gift and it needs to be taken care of. To be clear in one’s ideas, and to be responsible for them, is a token of spiritual freedom and intellectual joy.”

So, I encouraged Michael to work on some icons without any supervision on my part. The importance of being able to work in your own place of solitude is to develop one’s own internal dialogue in the contemplative exchange of being a believer and through the medium of the believer’s faith, the icon becomes the opening through which God can act directly in the believer as the cause of his or her comprehension of the icon. The tool for this concept in the icon painter’s world is the white gessoed panel. The white gessoed panel also symbolizes that the universe was created from emptiness and silence. Orthodox teaching calls the prayer of inner silence and tranquility, hesychasm, a way of life for every man or woman. The painting of an icon begins with this type of prayer, bringing the icon painter to a deeper level of realization and peace, separated from influences around him/her.

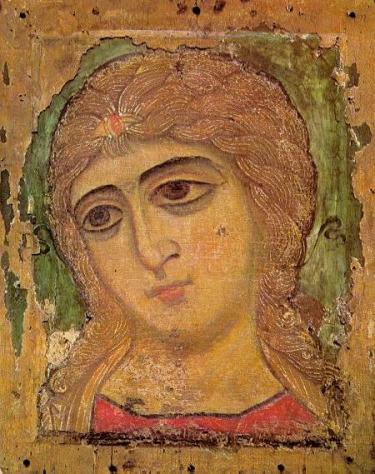

One of the icons that Michael was drawn towards is the icon of The (Arch)angel With the Golden Hair. The original icon:

is dated to the Novgorod School (1130-1190). This icon is at the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia.

The gold highlights (assist) used by the painter to outline and decorate the locks of hair on the angel gave the icon its name. The painting adheres itself to the style of Kievan art which carries a greater monumental quality in its personages. The eyes of the angel are soft and seem to be looking past the viewer. There is a certain sadness and compassion in the eyes, possibly indicating the knowledge of the ills of this world and a desire to ease the pain of the believers. This kind of detached look reminds us that eternal life is promised to those who suffer for Christ or remain faithful through many trials. The jewel in the angel’s hair may indicate that this is not an ordinary angel (which would be quite unusual for icon painting) but one of the Archangels, probably Michael or Gabriel. The shadows under the eyes, and the overal shape and size of the eyes lend themselves to comparisons with the funeral portraits of Fayum and to the best early icons discovered at the Monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai.

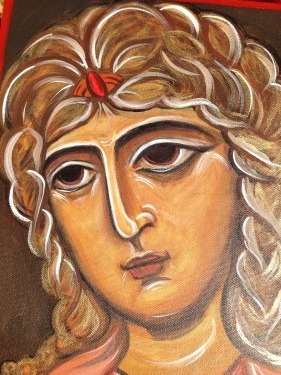

This image is Michael’s interpretation of the icon of The (Arch)angel With the Golden Hair

No comments yet.